Without prompt action, the United States' aviation system is headed toward gridlock shortly after the turn of the century. If this gridlock is allowed to happen, it will result in a deterioration of aviation safety, harm the efficiency and growth of our domestic economy, and hurt our position in the global marketplace. Lives may be endangered; the profitability and strength of the aviation sector could disappear; and jobs and business opportunities far beyond aviation could be foregone.

Currently, the aviation sector of our economy is vibrant and growing. At its core are technological innovation and managerial success. U.S. aircraft manufacturing leads the global market, and U.S. airline operations are the most competitive and efficient in the world. Our airports are recognized as professionally managed enterprises that are the engines of local and regional economies. The system is a true "public-private partnership," as air transport services, carrying passengers and freight, are produced by a combination of private firms and public agencies.

The private firms, passenger and cargo carriers, provide the equipment and crews that actually move people and goods, as well as the required support services-reservations and booking, ticketing, and baggage handling. The public agencies, the FAA, to a limited extent DoD, and airport authorities, provide the infrastructure of facilities, technology and services necessary for the safe and efficient operation of a large number of commercial aircraft, frequently in heavy-traffic conditions. The FAA provides the civilian air traffic control (ATC) system, including facilities, personnel, hardware and software. The airport authorities provide runways, terminal buildings (often in partnership with air carriers) and extensive support facilities.

In just the past several decades, this partnership has moved aviation from a minor industrial sector to being 6% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). U.S. airline and aerospace industries directly employ approximately 1.5 million people, mostly in highly skilled, high-wage jobs that generate more than $100 billion a year in wages.

According to the 1997 World Development Survey, the world's air travelers are expected to double from one billion to more than two billion over the next twenty years. The total economic impact of air transport on the world economy was $1.14 trillion in 1994. This is expected to increase to $1.7 trillion by the year 2010. Presently, over $1.5 trillion worth of freight is moved through the air around the globe annually.

The aviation system offers one of the most significant engines for national economic growth. If managed well, this economic advantage will become ever more important as there is continued movement toward a global economy dominated by services and lighter, high-value manufacturing.

There are dark storm clouds on the horizon, however. Our ability, as a nation, to provide the financial and management resources needed to support the underlying infrastructure (that is, our air traffic system and airports) and keep the aviation system vibrant and growing is slowly, but steadily, evaporating. The present process by which the air traffic control system and federally-related airport development is financed and managed will not meet the future needs of the national economy and the traveling public.

The effects are already being felt, but our current problems pale in comparison to what is anticipated to come in a few short years. What happens in the aviation sector of our economy will have an enormous impact beyond that 6% of the GDP. The problems that this country faces could be wide ranging because the rest of the GDP and its productivity have become inextricably linked to our aviation system. Try to picture our economy with a gridlocked aviation system and what could and could not be produced.

The problem is difficult to solve because it is multifaceted and the solution requires dramatic changes in the way the business of air traffic control and federally related airport development is conducted. The Congress, the Executive Branch, the FAA, and the aviation community will all have to be part of the changes. The solution is all the more difficult to achieve because long-standing institutional relationships must be dramatically altered if our nation is to avoid the problem that is about to be delivered on its doorstep.

The U.S. air traffic control system does not have enough capital resources to overhaul its technological components as quickly as needed and to continue operating on a day-in-and-day-out basis at a tempo that the public expects and that economic activity and growth require. Similarly, our airports need more federally-related resources to meet the future capital requirements that growth in air transportation will demand.

Just focusing on financial resources, however, would dramatically understate the problem confronting our country. How we organize, manage, make plans for, and execute critical decisions about the future of this basic building block of our economy is just as significant. Sweeping organizational, institutional, and management changes are also required. Money alone is not the answer.

Every day that passes without financial and management reforms means the coming gridlock will be here sooner and last longer than if the country steps up to the problems now. The U.S. air transportation system is falling into a hole that will take a great deal of money and time to climb out of. We, as a nation, still have a grip on the edge of that hole, but significant steps need to be taken very soon or that grip will be lost. Not just aviation will be pulled into the pit. Because aviation has become such a normal and ubiquitous part of our economic way of life, nearly every other sector of our economy will find itself dragged into it in one degree or another.

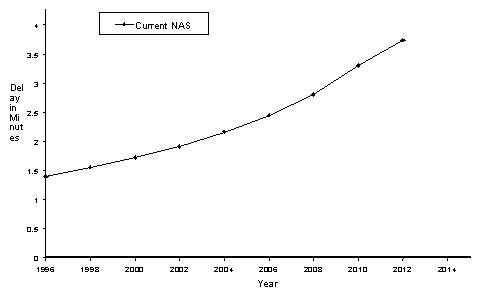

As stated above, the problems with the financing and management of our air traffic control system are already becoming manifest. In 1995, the FAA estimated that airline delays cost the industry approximately $2.5 billion per year in higher operating expenses. That cost is clearly higher today and will grow. Recent data indicate the delay problem is getting worse. The number of daily aircraft delays of 15 minutes or longer was 18.9% higher in 1996 than in 1995. As illustrated in figure 1, American Airlines data shows that delays are likely to grow at ever-increasing rates unless some action is taken soon. American Airlines has estimated that by 2014 it expects delays to increase by a factor of three, bringing its hub and spoke system to its knees.

Figure 1.

Moreover, delays appear to be lengthening. The Air Transport Association reports that the amount of time per delay rose 10% between 1995 and 1996. However, this figure masks the problem, because delay has become such a normal operational feature of the air traffic control system, airlines have simply built additional time into their flight schedules to accommodate it.

While extremely costly, delays in the air traffic and airport system will soon move beyond a cost and an inconvenience to be borne to a major breakdown of our air transportation system. Most major airlines operate with a hub and spoke route system or require quick turnaround times at gates. The efficiency and efficacy of these approaches are entirely dependent on the ability to reliably and dependably schedule flights to arrive at and leave airports in relatively narrow windows of time. The uncertainty these delays create are occurring at the same time that today's economy requires better reliability and predictability. There are at least three significant and rising costs from a system which is approaching gridlock:

For example, air traffic inefficiencies cost Delta Air Lines approximately $300 million per year. Delta Air Lines estimates that if just four more minutes are added to the average time of each flight, it will not be able to reliably operate its hubs. The foundation of Southwest Airlines' low-fare operation is a 20-minute turnaround between flights. If just five minutes are added to its turnaround time, Southwest would be forced to fly each of its aircraft one less flight per day, jeopardizing its ability to continue to offer low-fares. A recent MITRE Corporation analysis confirms these projections and estimates. As airlines strive to maintain the reliability of their operations, the result will inevitably be reductions in air service with the attendant negative economic impact.

Given the delay and congestion problems that already exist, anticipated growth, without needed expansion of capacity in the air and on the ground, will simply reach a point at which it cannot be accommodated. Historically, the growth of aviation has outpaced overall economic growth. For example, in 1996, the strong U.S. economy (growing, at approximately 3%) spurred domestic airline traffic to grow 6.6%.

Many will recall that in the 1980s growth in aviation was constrained by the failure to rebuild the air traffic control workforce after the 1981 strike. The air transportation system was widely viewed as hitting a ceiling in terms of moving people and shipments smoothly, effectively, and efficiently. A similar situation awaits us, albeit for different reasons, but the result will be the same and likely worse.

Every forecast of aviation activity predicts steady growth well into the next century. U.S. domestic and international passenger enplanements are expected to increase by 52% between 1996 and 2006 (from 606 million to 920 million). For the next ten years the FAA forecasts that annual growth in revenue passengers miles will average 4.2%. Aircraft movements are also expected to dramatically rise. In 2008, there are forecast to be nearly 10 million more annual aircraft operations than the 63 million operations expected by the end of this year. While aviation activity is growing. the FAA's capital investments are decreasing. Between 1992 and 1997, the effective buying power of the FAA's capital budget has decreased nearly 40%.

In short, growth, without significant capacity improvements, is already posing a serious challenge to the efficiency of our air transportation system, and hence the economy at large. Continued steady growth, without adequate investment in the air traffic control and airport system, will make this challenge even more daunting with each passing day. At some point, the challenge will become completely unmanageable, and growth in aviation will stop. The effect of this will ripple throughout the economy affecting, other sectors' ability to grow.

As mentioned above, the aviation system has become integral to the national and global economics. Virtually all sectors of the economy are now dependent on air transportation for the movement of goods and people. Approximately half of air travel is undertaken in the course of conducting business. Even in the face of new and improved electronic and telephonic means of communication, air travel continues to grow indicating that face-to-face communication remains a necessity for business transactions. In short, the aviation system has become a basic element of the infrastructure of the nation's and the world's economic way of life. Significant problems that cause inefficiency in the air transportation system will hinder the ability of businesses to open new markets and create new opportunities to expand and grow.

The FAA has both large capital requirements and large day-to-day operating needs. The FAA is unique for a government agency in that it provides around-the-clock, 365-days-a-year air traffic control services -- a linchpin of our nation's economic well being. However, the FAA is funded and budgeted like other government agencies, most of which do not have this type of operating responsibility.

Being subject to the increasingly stringent federal budgetary caps , the agency is placed in the unsustainable position of having to forego capital development programs in order to keep the day-to-day operations adequately staffed. The FAA's capital investments have decreased by approximately 20% since FY 1992, while funding for operations has increased by more than 10% over the same period.

In recent years, this predicament has forced the FAA to cut back on airport grants and forego full investment in modernizing air traffic control equipment. A process that forces the agency to be shortsighted will inevitably harm the entire aviation system in the long term. Unfortunately, the long-term consequences are actually just around the comer.

Unless the budgeting and funding picture is dramatically altered so that aviation revenues can be directly linked to the programs they ostensibly support, rising operating expenses will outstrip the FAA's ability to make capital investments in air traffic control and airports. When faced with limited resources. operating and maintaining the present system prevails over the need to modernize.

Operating expenses are climbing because of traffic growth in the system and the rising costs of maintaining a large inventory of antiquated equipment. Because much of the equipment is old, its failure rates and outage intervals are resulting in ever-increasing maintenance costs as FAA strives to keep the. equipment up and running. Just between 1992 and 1996, the number of hours of unscheduled outages more than doubled. When budget constraints guide policy choices in this kind of operating environment, the inevitable result is a downward spiral of disinvestment and increased operating costs. This is painfully ironic since one of the principal reasons for capital investment is to reduce the growth in the operations budget.

The problems of the current budget predicament were brought home to the aviation community when the recent 5-year federal budget agreement was enacted into law. It raises an extra $4 billion from the aviation community (including passengers and shippers), all of which will be deposited into the Airport and Airway Trust Fund. Although the aviation users will pay significantly more in taxes, there are no guarantees that the funds will be spent on aviation purposes. The current budget caps and rules will likely result in the extra revenue only being locked up in the Trust Fund, unavailable to be used to develop and operate the system. Virtually all of the new revenue will be used to off-set spending on non-aviation programs, setting a very damaging precedent for the future.

The likely effect of the recent budget agreement on the near-term funding of these programs makes change imperative. The case becomes even stronger if the longer term effects of the budget agreement lead to the federal deficit beginning to climb after 2002. If that happens, the FAA's programs will come under even greater pressure just as the congestion and delay crises described above are beginning to strangle the national air transportation system and the overall economy.

In the face of growing demands on airport infrastructure because of the passenger and traffic growth described above, safety and environmental requirements, and the continual need to refurbish existing infrastructure so as not to lose it, the federal government's role in providing airport capital investment has actually slackened in recent years. Between 1992 and 1996 the annual program was reduced by nearly $500 million, or 23%. For FY 1998 it appears the Congress will fund AIP at $1.7 billion, but this is well below the authorized amount.

While the congressional appropriations process may well provide a greater amount than that requested by the President for next year, the uncertainty and instability that pervades the airport funding picture has reached such a level that local planning is virtually impossible to accomplish in some circumstances. This has resulted in the delay or deferral of capacity-critical projects.

The budgeting and funding process has become so flawed that the aviation community finds itself standing up and cheering when an extra $250 million in airport grants are available, even though that restores the program to $200 million shy of its highest level of $1.9 billion, and $500 million below where most believe it should be to support 3,400 airports.

Such underinvestment will certainly lead to further congestion in the aviation system. In 1995, 25 of the largest U.S. airports were characterized as "severely congested" by the FAA. Without adequate capacity enhancements, this number will climb to 29 by 2005. Among those airports that would newly achieve this dubious distinction are Baltimore-Washington, San Diego, and Memphis. Each of the nation's ten most congested airports averaged more than 3,000 hours of delay per month for the first four months of this year. This will continue and only get worse if adequate infrastructure is not developed.

In 1990, a new source of airport development funds was created, known as passenger facility charges (PFCs). These are locally levied charges of up to $3 per passenger for specific airport capital improvement projects. While the FAA has no role in collecting these funds, it does approve specific projects before a PFC can be levied. When PFCs were established, it was for the purpose of creating a whole new funding stream on top of the AIP. In some respects, with the AIP falling off in recent years because of the overall budget situation, the PFC program has come to act largely as a replacement for AIP funds in the minds of aviation policy makers in the Executive and Legislative Branches. This mind set is hurting both of these vitally important programs.

The Commission believes that underinvestment in airport infrastructure undermines the benefits that can be expected through modernization of the air traffic control system. If airport and air traffic investments do not keep pace with one another, capacity gained on the air traffic side cannot be fully realized. Whether an aircraft is delayed because of a lack of runway, taxiway, or terminal constraints, or if it is because of inadequate air traffic control equipment, the effect on the traveling public and the broader economy is the same: higher costs, lost productivity, and poorer economic performance.

Aviation users perceive a lack of connection between, the FAA's management of the air traffic control system, and the agency's ability to reduce the cost of operating in the system. The aviation community has lost faith that the FAA can meet their needs for lower operational costs. This has manifested itself in significant ways and at great cost.

Fifteen years ago, the FAA embarked on a program to modernize the air traffic control system. Unfortunately, the agency looked at itself as the "customer" of the system, rather than those who pay to use it. This approach led to a collection of overly ambitious, out-of-scope, too expensive, and undermanaged projects that have fallen years behind schedule with cost overruns in multiples of their original projections. For the most part, when these projects are finally delivered, there will be no additional system performance or capability from the users' perspective, no reduction in costs to use the system, and few improvements in safety. The follow-on programs to the Advanced Automation system (AAS), for example, will provide the same basic functionality of today's systems on modern hardware. While system outages and breakdowns are expected to decrease, without a change in acquisition philosophy, new tools designed to enhance controllers' productivity will not be implemented for a least another 5 years.

Another recent example of how this approach continues is seen in the Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS) program, which makes satellite navigation signals accurate and reliable enough to be used in commercial aviation. The airline industry, which WAAS is supposed to benefit, was never fully supportive of the FAA's approach to the problem this program was intended to solve. The program is perceived to be troubled with costs and schedules under review. These difficulties, coupled with an industry skeptical of the FAA's approach even if it was working properly, undermine aviation stakeholders' confidence in the FAA's ability to meet their needs at a reasonable price.

If there is any hope in the near term of making improvements that provide significant benefits to air travelers, shippers, and other users of the system, the air traffic control system (including its capital investment) must become managed from a perspective that enables its performance to be continually assessed and improved. Without this change, critical safety and operational problems loom in the immediate future.

Part of the disconnect between the FAA's management of the air traffic control system and the user community resides in the inability of both the FAA and its users to assess and act upon the true costs of their plans and actions. This approach has led new projects and procedures to be launched and ongoing projects and procedures to be continued without proper and crucial management knowledge and user input and support.

Better data on the costs of specific air traffic control services and pricing mechanisms related to that data will send better economic and market-type signals to both FAA managers and the industry. This would improve decision-making by forcing both to examine whether there were better, less expensive ways to provide the service, or whether the service was really worth the costs from the users' perspective.

Because system delays and congestion are related to the most heavily used components of the aviation system, additional resources (capital or operational) in particular places will undoubtedly yield system-wide benefits. A better allocation of existing funds for needed investments or operational changes could make a real difference in solving these problems. Currently, however, such information about system needs is incomplete at best.

In a free market, businesses can look at the revenues and costs of services and product lines and learn a great deal about how customers value products relative to their costs, where cost savings can be found, where to make improvements, and the most attractive opportunities to invest new capital. At present, there is a dearth of this kind of information flowing in either direction between the FAA and its customers. An approach is required that mimics the information and resources that market price signaling provides the private sector, so that best business practices and management can be brought to bear on a system that is so important to the nation's economic well being. A move toward a system that is able to convey market-like financial and economic-like signals would help FAA better manage the day-to-day air traffic control operation and develop an investment strategy for the future that is more sophisticated than "more is better."

The Commission believes that without a fundamental change in management practices and perspective, coupled with cost-based accounting and financing mechanisms, the management of the ATC system will be largely focused on evolving day-to-day operations, without the foresight to implement long term improvement strategies. The costs of continuing in this fashion are enormous and not sustainable.

Since the dawn of aviation, it has been said that the U.S. air traffic control system is second to none. There are already indications that this may no longer be the case. Numerous other countries are taking steps to improve airport facilities dramatically and modernize air traffic control systems with state-of-the-art technology. The irony is that, more often than not, these countries are procuring advanced technology from U.S. companies that have been unable to sell their wares to the FAA. The irony is compounded by the U.S. exporting advanced air traffic equipment, while the FAA imports vacuum tubes to run some of its antiquated equipment. This predicament is due in part to cumbersome procurement rules (from which the FAA was recently freed), lack of good management approaches and practices, the absence of a steady and reliable funding source, and a budgeting process that tilts away from taking the long view.

Because of the FAA's lack of modern ATC equipment, there have been suggestions in International Civil Aviation Organization forums about redelegating oceanic ATC responsibilities that now rest with the United States. Canada, Germany, Norway, the United Kingdom, and some Asian, Latin American, and Eastern European countries are installing and, in some cases, are now using state-of-the-art equipment. Although 19 out of 20 of the busiest airports in the world are in the U.S., the United States can no longer claim that it has the world's most modern air traffic control system.

This was further underscored in an Aviation Week article from January 27, 1997 describing a variety of satellite navigation developments that have been initiated by the island nation of Fiji. The article stated: "The United States is being left behind in the implementation of satellite navigation and digital data communication for air traffic management in the Asian/Pacific areas."

Other countries are also making multi-billion dollar investments to upgrade and build new airports. As examples, whole new airports representing investments of billions of dollars are being built in Asia. Existing ones are being refurbished and given new capacity. Osaka and Munich recently opened new airports. These investments are being made because there is a recognition that to compete well in the global economic system markets need to be served with strong airport infrastructure. While the U.S. recognizes this need as well, the present funding system forces the country to invest less than it should on capital investment at airports.

For the United States to compete well in the global marketplace this picture must change dramatically. If it does not, the U.S. simply should not expect to have an aviation system that provides competitive benefits.

Outdated technology and ever increasing capacity demands placed on our airports and air traffic control system can have an impact on safety. As the pace of activity quickens and greater demands are placed on our aging communication, navigation and surveillance equipment, failures are bound to occur. Antiquated backup systems cannot be expected to provide needed safety assurance as communication and radar failures become a more frequent occurrence.

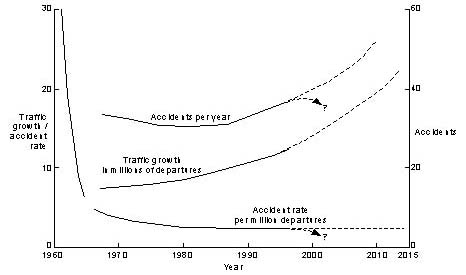

Maintaining old equipment and responding to capacity demands are not, therefore, simply economic efficiency issues. Like old bridges and congested highways, congested airports and airways supported by outdated equipment can be less safe. A system straining at the seams of capacity is one that is also straining to be safe. Even aside from congestion posing risks, sheer growth is going to result in more accidents if nothing is done to dramatically reduce the accident rate. A Boeing Company analysis (as shown below) found that when today's accident rate is applied to the traffic forecast for 2015, the result would be an airliner crashing somewhere in the world almost weekly. If the problems caused by congestion and failing equipment are laid over this, it presents a safety problem which the public will find intolerable.

Figure 2.

To summarize, this report will set out a path to steer us away from the looming disaster. Those who are prepared to argue that this path should not be followed, must be ready to offer a viable alternative, because staying on the present path is untenable. The American public deserves better than gridlock in the sky and congestion on the ground. The Commission's recommendations will change the current course and lead to a stronger aviation system in the future. The nation will be more prosperous and the traveling public will be safer if the recommendations of the National Civil Aviation Review Commission are adopted.

| Return to Avoiding Aviation Gridlock: A Consensus for Change Index |